Pygmy in the Monkey House

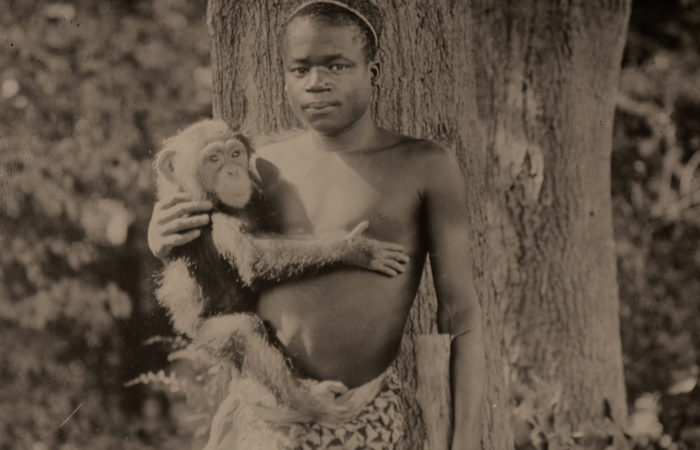

Ota Benga

Purchased at a slave market in Africa by minister-turned-explorer Samuel Verner, Ota Benga was a member of the Mbuti people, an indigenous group of pygmies who lived in the African Congo. Benga was first brought to America by Verner to be put on display with other indigenous peoples at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Benga was later brought back to America by Verner in 1906 and was displayed in the Monkey House of the Bronx Zoo. The exhibit attracted hundreds of thousands of people and created a firestorm of controversy. After widespread protests by clergy, Ota Benga was ultimately transferred to the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, and later to a Seminary in Lynchburg, Virginia. Benga wanted to return to his native Africa, but World War 1 prevented him from doing so. In 1916, Benga shot himself to death.

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

“Ota Benga’s Short, Tragic Life As A Human Zoo Exhibit” (Article)

Original Newspaper Coverage:

“Bushman Share a Cage with Bronx Park Apes,” The New York Times, September 9, 1906.

“Legal Fight for Pygmy,” The New York Times, September 13, 1906

“African Pygmy’s Fate Is Still Undecided,” The New York Times, September 18, 1906

“Pygmy to Be Kept Here,” The New York Times, September 19, 1906

“Ota Benga Attacks Keeper,” The New York Times, September 25, 1906

“Pygmy Officially Viewed,” The New York Times, September 27, 1906

“Colored Orphan Home Gets the Pigmy,” The New York Times, September 29, 1906

“Hope for Ota Benga; If Little, He’s No Fool,” The New York Times, September 30, 1906

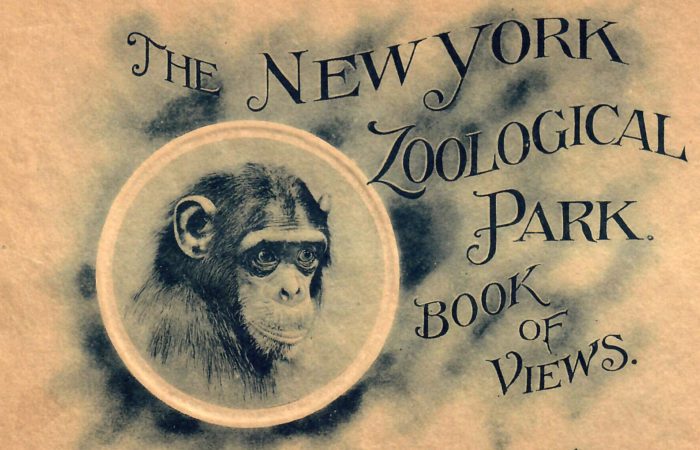

Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (officially, the New York Zoological Park) had been envisioned by its founders as the largest zoo in the world and “the grandest zoological establishment on earth.” The zoo was directed by zoologist William Temple Hornaday, who had formerly worked at the Smithsonian. Overseeing Hornaday was an Executive Committee chaired by Henry Fairfield Osborn, a distinguished professor at Columbia University. Hornaday and Osborn had dreams of exhibiting more than just animals at their new zoo.

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

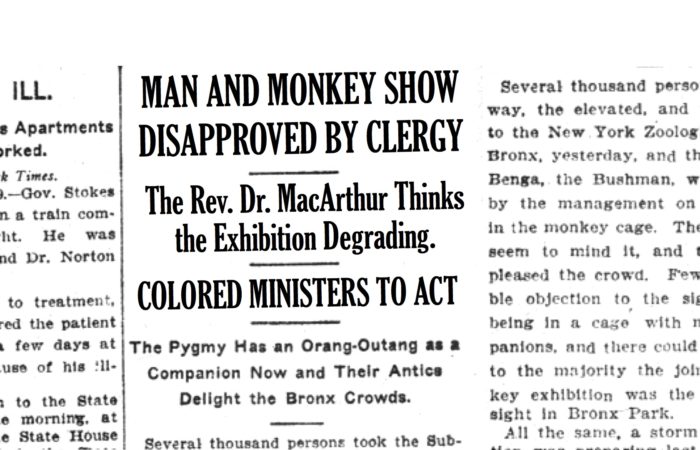

Clergy

Many members of New York’s clergy were horrified by the public display of Ota Benga in the Monkey House. First to speak out was the Rev. Robert Stuart MacArthur, pastor of the city’s Calvary Baptist Church, one of the largest Baptist congregations in America. One of the most articulate and determined critics of the zoo display was African-American minster James H. Gordon, Superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn.

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

Original newspaper coverage:

“Negro Clergy Protest,” New–York Daily Tribune, September 11, 1906

“Man and Monkey Show Disapproved by Clergy,” The New York Times, September 10, 1906

“Negro Ministers Act to Free the Pygmy,” The New York Times, September 11, 1906

“The Mayor Won’t Help to Free Caged Pygmy,” The New York Times, September 12, 1906

“Still Stirred about Benga,” The New York Times, September 23, 1906

Media

New York’s most prominent newspaper—The New York Times—was largely unsympathetic to Ota Benga’s plight and even professed to be puzzled by the anger of those who protested Benga’s demeaning treatment. “We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter,” editorialized the Times. Describing African pygmies as “very low in the human scale,” the Times made clear that it viewed pygmies as less than fully human. The editors at the Times also thought it “absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation… [Ota Benga was] suffering.” In fact, they claimed the pygmy was “probably enjoying himself.”

After African-American ministers criticized the Zoo for trying to use Ota Benga to prove Darwinian evolution, the Times weighed in again. “To find that there are still alive those who do not accept” Darwin’s theory was “startling” according to the Times. “The reverend colored brother should be told that evolution, in one form or another, is now taught in the text books of all the schools, and that it is no more debatable than the multiplication table.”

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

Original newspaper coverage:

“Send Him Back to the Woods,” The New York Times, September 11, 1906

“The Pigmy Is Not the Point,” The New York Times, September 12, 1906

“Ota Benga, Pygmy, Tired of America,” The New York Times, July 16, 1916