Explore

Eugenics

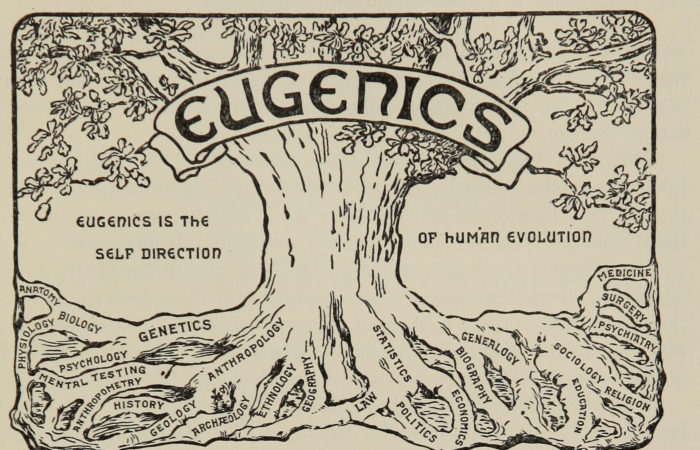

Eugenics was the science of breeding better humans based on Darwinian principles. It was supposed to allow humanity to take control of its own evolution by breeding a better race. In the words of Horatio Hackett Newman, a University of Chicago Zoology Professor, through eugenics “man might control his own evolution and save himself from racial degeneration.” The term itself was coined by Charles Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton. “Positive eugenics” focused on encouraging those deemed the most fit to reproduce more, while “negative eugenics” focused on curtailing reproduction by those deemed unfit, including mental defectives, criminals, and non-whites.

Eugenics was widely embraced by leading evolutionary biologists, doctors, and politicians in the early years of the twentieth century. Promoters of eugenics in America included scientists at Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Columbia, Stanford, the University of Chicago, the National Academy of Sciences, and many other institutions.

For more information:

Darwin Day in America by John G. West (Book)

The Eugenics Archive (Website)

Charles Darwin

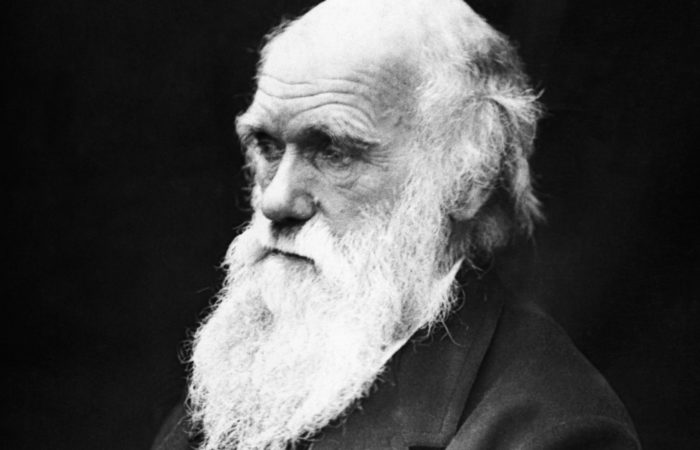

Charles Darwin is best known for formulating the theory of evolution by natural selection. The heyday of eugenics came after Charles Darwin’s death, but Darwin helped supply the rationale for eugenics in various passages in his book The Descent of Man, where he warned that “civilized” societies were undercutting natural selection and destroying themselves by saving the sick, helping the poor, vaccinating people against small-pox, and allowing their worst members to breed. Darwin did go on to caution that humans can’t follow the dictates of “hard reason” in such cases without undermining their “sympathy… the noblest part of our nature.” At the same time, he expressed hope that natural selection would in fact continue to eliminate those he considered a drag on society. Scholars continue to debate how much support Charles Darwin lent to Social Darwinism. Charles Darwin’s son Leonard later became the Chairman of the British Eugenics Society for many years, and he spoke at the Second International Congress of Eugenics in New York City in 1921.

American Museum of Natural History

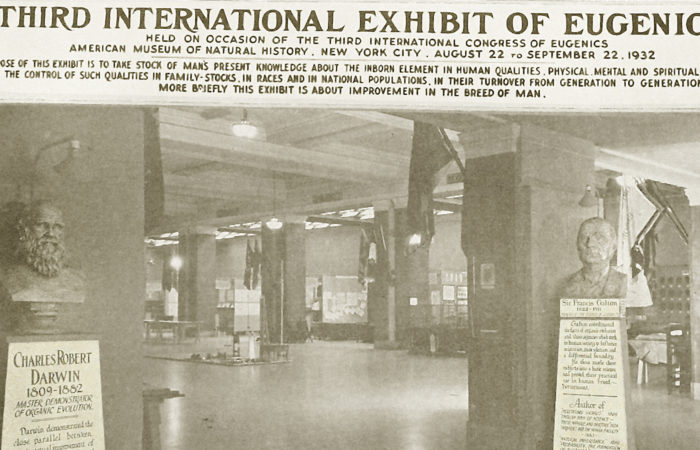

The American Museum of Natural History in New York City remains one of the world’s leading natural history museums. During the early part of the twentieth century, it was also one of the nation’s leading proponents of eugenics. Under the direction of paleontologist and eugenist Henry Fairfield Osborn, it even hosted the Second International Congress of Eugenics in 1921 and the Third International Congress of Eugenics in 1932.

Eugenics Record Office

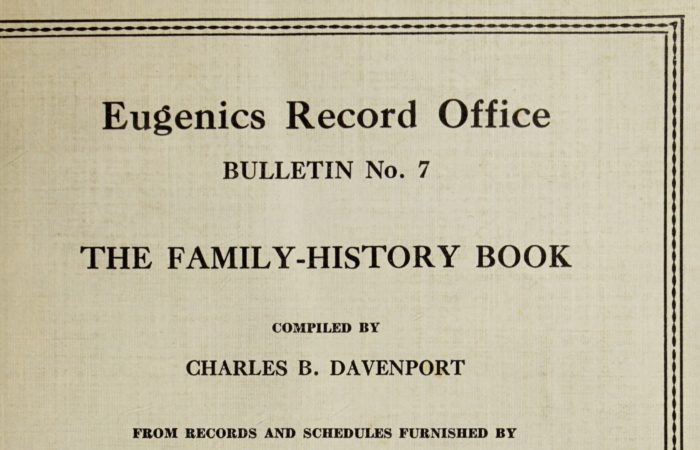

Founded by National Academy of Sciences geneticist Charles Davenport, the Eugenics Record Office was one of the most virulent American eugenics organizations. It was established in 1910 at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, still one of the world’s preeminent biological research institutions.

For more information:

“When Racism Was a Science” (Article/New York Times)

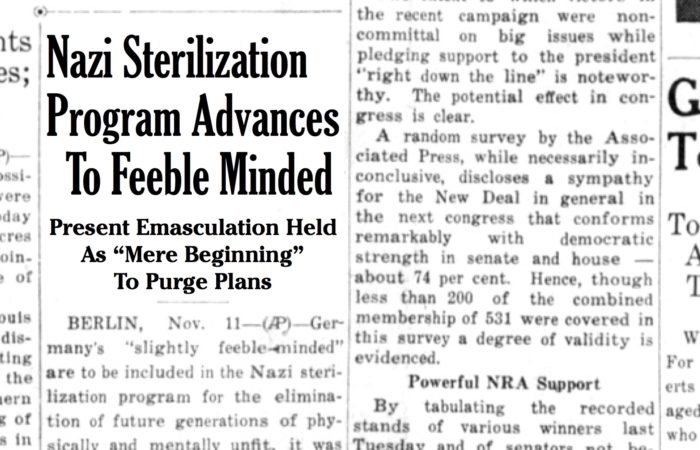

Nazi Eugenics

Drawing on the ideas of Social Darwinism, Nazi racial theory dehumanized the handicapped, Jews, and many other groups as drags on German society. Most people know that the Nazis exterminated more than six million Jews. But they also enacted an extensive eugenics program, which led to the sterilization of hundreds of thousands of people and the gassing of the mentally handicapped as well. Nazi eugenics efforts received praise from leading supporters of eugenics in America.

For more information:

“Victims of the Nazi Era: Nazi Racial Policy” (Article/US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

“The Role of Darwinism in Nazi Racial Thought” (Article/German Studies Review)

“Hitler, Darwin and the Holocaust: How the Nazis Distorted the Theory of Evolution” (Article/Salon.com)

“Medical Science Under Dictatorship” (Article/New England Journal of Medicine)

“GERMANY: Praise for Nazis” (Article/Time)

“Eliminating the Inferior: American and Nazi Sterilization Programs” (Article/Institute for the Study of Academic Racism)

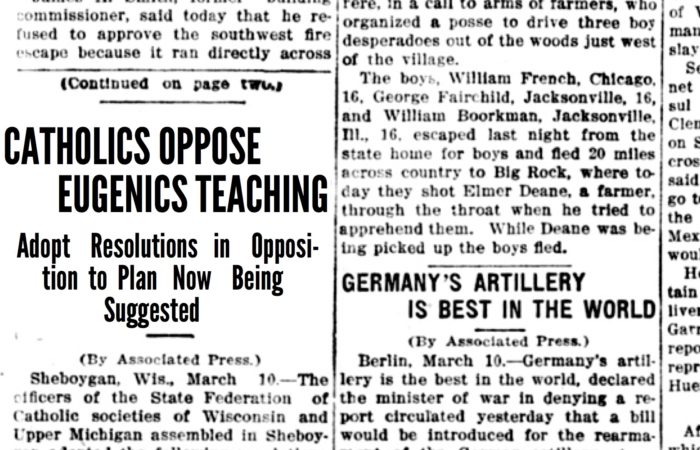

Opposition to Eugenics

Some scientists became skeptical of eugenics as time went on, but much of the opposition to eugenics came from traditional religious communities, especially Catholics and some evangelical Protestants. In 1930, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical Casti Connubi, which condemned eugenics. By contrast, more theologically liberal clergy often supported eugenics.

“Catholics and Eugenics: A Little-Known History” (Article/National Catholic Reporter)

Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement by Christine Rosen (Book)

“Interview with Christine Rosen” (Interview/Center for Bioethics and Culture Network)

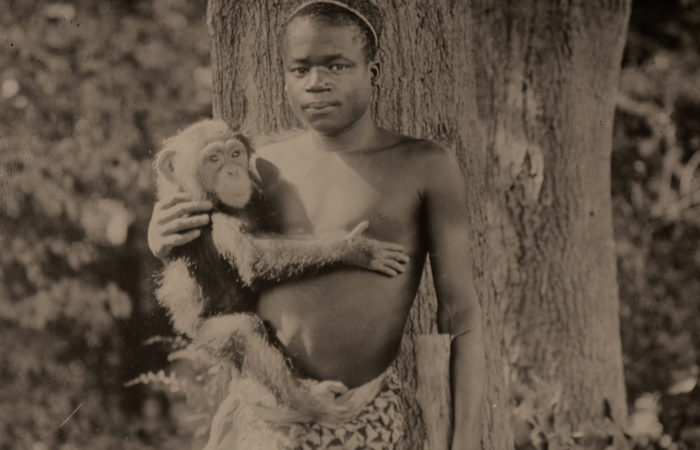

Ota Benga

Purchased at a slave market in Africa by minister-turned-explorer Samuel Verner, Ota Benga was a member of the Mbuti people, an indigenous group of pygmies who lived in the African Congo. Benga was first brought to America by Verner to be put on display with other indigenous peoples at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Benga was later brought back to America by Verner in 1906 and was displayed in the Monkey House of the Bronx Zoo. The exhibit attracted hundreds of thousands of people and created a firestorm of controversy. After widespread protests by clergy, Ota Benga was ultimately transferred to the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, and later to a Seminary in Lynchburg, Virginia. Benga wanted to return to his native Africa, but World War 1 prevented him from doing so. In 1916, Benga shot himself to death.

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

“Ota Benga’s Short, Tragic Life As A Human Zoo Exhibit” (Article)

Original Newspaper Coverage:

“Bushman Share a Cage with Bronx Park Apes,” The New York Times, September 9, 1906.

“Legal Fight for Pygmy,” The New York Times, September 13, 1906

“African Pygmy’s Fate Is Still Undecided,” The New York Times, September 18, 1906

“Pygmy to Be Kept Here,” The New York Times, September 19, 1906

“Ota Benga Attacks Keeper,” The New York Times, September 25, 1906

“Pygmy Officially Viewed,” The New York Times, September 27, 1906

“Colored Orphan Home Gets the Pigmy,” The New York Times, September 29, 1906

“Hope for Ota Benga; If Little, He’s No Fool,” The New York Times, September 30, 1906

Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (officially, the New York Zoological Park) had been envisioned by its founders as the largest zoo in the world and “the grandest zoological establishment on earth.” The zoo was directed by zoologist William Temple Hornaday, who had formerly worked at the Smithsonian. Overseeing Hornaday was an Executive Committee chaired by Henry Fairfield Osborn, a distinguished professor at Columbia University. Hornaday and Osborn had dreams of exhibiting more than just animals at their new zoo.

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

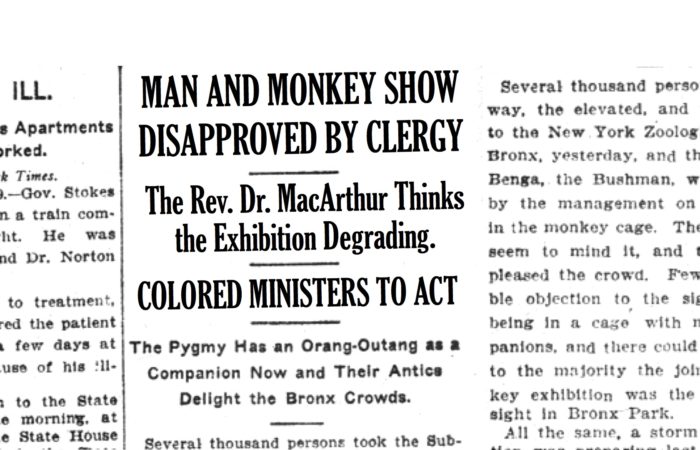

Clergy

Many members of New York’s clergy were horrified by the public display of Ota Benga in the Monkey House. First to speak out was the Rev. Robert Stuart MacArthur, pastor of the city’s Calvary Baptist Church, one of the largest Baptist congregations in America. One of the most articulate and determined critics of the zoo display was African-American minster James H. Gordon, Superintendent of the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn.

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

Original newspaper coverage:

“Negro Clergy Protest,” New–York Daily Tribune, September 11, 1906

“Man and Monkey Show Disapproved by Clergy,” The New York Times, September 10, 1906

“Negro Ministers Act to Free the Pygmy,” The New York Times, September 11, 1906

“The Mayor Won’t Help to Free Caged Pygmy,” The New York Times, September 12, 1906

“Still Stirred about Benga,” The New York Times, September 23, 1906

Media

New York’s most prominent newspaper—The New York Times—was largely unsympathetic to Ota Benga’s plight and even professed to be puzzled by the anger of those who protested Benga’s demeaning treatment. “We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter,” editorialized the Times. Describing African pygmies as “very low in the human scale,” the Times made clear that it viewed pygmies as less than fully human. The editors at the Times also thought it “absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation… [Ota Benga was] suffering.” In fact, they claimed the pygmy was “probably enjoying himself.”

After African-American ministers criticized the Zoo for trying to use Ota Benga to prove Darwinian evolution, the Times weighed in again. “To find that there are still alive those who do not accept” Darwin’s theory was “startling” according to the Times. “The reverend colored brother should be told that evolution, in one form or another, is now taught in the text books of all the schools, and that it is no more debatable than the multiplication table.”

For more information:

Spectacle: The Astonishing Life of Ota Benga by Pamela Newkirk (Book)

Original newspaper coverage:

“Send Him Back to the Woods,” The New York Times, September 11, 1906

“The Pigmy Is Not the Point,” The New York Times, September 12, 1906

“Ota Benga, Pygmy, Tired of America,” The New York Times, July 16, 1916