St. Louis World’s Fair

The World Comes to St. Louis

Known officially as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, the St. Louis World’s Fair ran from April 30-December 1, 1904 and was one of the most famous international expositions held in the United States in the early twentieth century. Attended by more than 19 million people, the Fair was known for its lavish neo-classical buildings, its 22-story-high Ferris Wheel, and the public debut of innovations such as the x-ray machine and the ice cream cone. But the fair had a darker side. Organizers imported thousands of indigenous peoples from around the world to be put on public display in what was essentially a giant human zoo. Unlike freak shows, the human zoo in St. Louis was created with the cooperation of America’s scientific establishment.

For more information:

The 1904 World’s Fair: Looking Backward at Looking Forward, Online Exhibition (Missouri Historical Society)

Louisiana Purchase Exposition Collection (Missouri History Museum)

Anthropological Displays

Anthropologist William McGee was a leading American scientist in the early 1900s. As head of the Anthropology Department at the St. Louis World’s Fair, he was determined to showcase indigenous peoples at the Fair to dramatize for the public the different stages of human evolution—beginning with races he considered lowest on the evolutionary scale. McGee arranged for native peoples to be put on display in “villages” designed to recreate their native habitats. These villages were enclosed by fences—making them truly seem like human zoos. More than 4 million fair-goers reportedly visited these anthropological displays, eagerly staring at and poking at the indigenous peoples in their enclosures. Adding to the indignities, native peoples were pressured to participate in a series of athletic contests designed to show they were biologically inferior to whites. Those on display were also subjected to experiments in a special laboratory set up by the Fair’s Anthropology Department. Directed by a psychology professor from Columbia University, the lab conducted tests to measure native people’s intelligence and physical features, and even their threshold for pain.

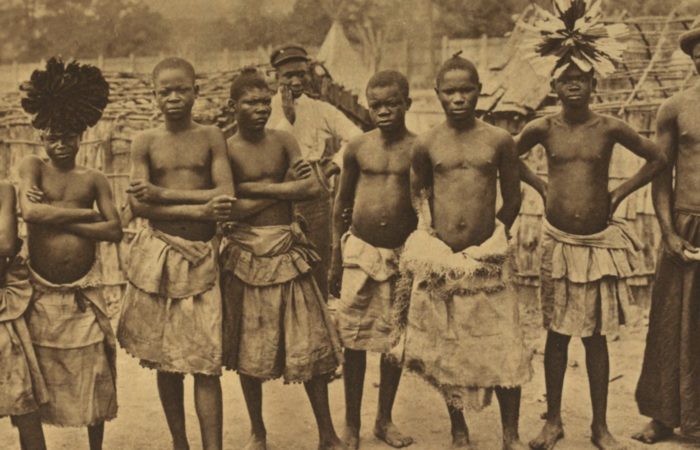

Native peoples were brought to the St. Louis exposition from the far corners of the globe. From Japan came representatives of the Ainu people. Patagonians came from South America. Igorotes and Negritos came from the Phillipines. Both were thought by scientists of the time to be near the bottom of the evolutionary ladder for humans. The Negritos were even marketed at the Fair as another “missing link” between humans and apes. But perhaps the most exotic people group brought to St. Louis for public display were Pygmies from the African Congo.

For more information:

Anthropology Goes to the Fair: The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition (Book)

“Olympic-Sized Racism” (Article/Slate)

Pygmies at the Fair

Pygmies put on display at the St. Louis World’s Fair had been transported from Africa by former missionary-turned-explorer Samuel Phillips Verner. The Fair’s anthropologist William McGee repeatedly compared the pygmies to monkeys and apes. In the journal Science, he even asserted that pygmies were “commonly considered to approach subhuman types more closely than any other variety of the genus Homo.” One Pygmy at the Fair became a special celebrity. His name was Ota Benga. Samuel Verner had purchased him at a slave market. At the end of the Fair, the Pygmies returned to Africa with Samuel Verner. But in 1906, Verner brought Ota Benga back to America.

For more information:

“Pygmies May Be the Missing Link” (Article/St. Louis Republic, July 1904)

Photos of Pygmies at the St. Louis World’s Fair (Missouri History Museum)